A Disorder of Regulation, Not Structural Damage

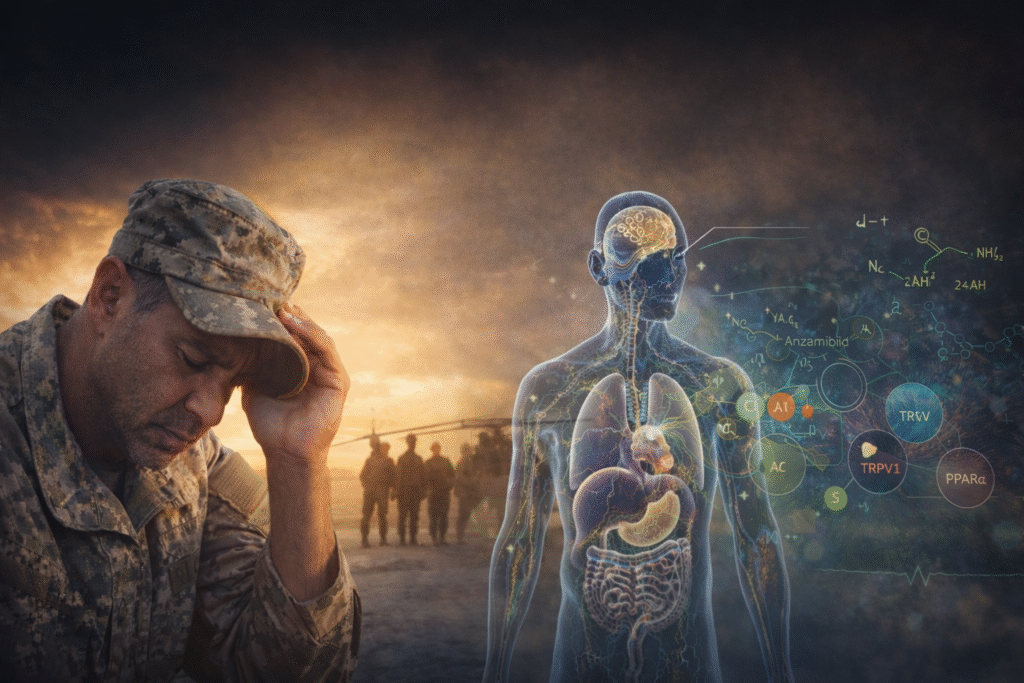

Gulf War Illness (GWI) has been a mystery for both doctors and patients. Veterans often report constant fatigue, sudden mood changes, mental fog, changes in their immune system, and a sense that their bodies never fully recover. Because there is no obvious physical damage, it has been hard to understand what this illness really is.

Emerging research is beginning to clarify the underlying regulatory physiology.

Gulf War Illness is better understood as a problem with how the body regulates itself, not as damage to a single organ or even an organ system. The main systems involved, the nervous, immune, autonomic, and stress-response systems, may still appear physically healthy. However, they do not work together as they should. The body does not fully recover from stress and stays slightly on edge.

All of these systems are strongly affected by the endocannabinoid system (ECS) and the larger network called the eCBome. When this network stops working smoothly, people can feel unwell even if there is no clear injury.

It may be less accurate to think of the body as damaged, and more accurate to understand it as functionally stuck.

Pyridostigmine Bromide and Latent Neuroimmune Reprogramming

One major suspected cause of GWI is exposure to pyridostigmine bromide (PB) during deployment. Early research suggests that PB may do more than cause short-term problems. It could lead to long-lasting changes in how the nervous and immune systems interact, especially between the gut and the brain.

Animal studies show that PB exposure changes how natural lipid messengers like palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) control inflammation and nerve signals. These changes affect TRPV1 signaling, endocannabinoid balance, and PPARα anti-inflammatory pathways. The result appears to be a latent, sex-dependent neuroimmune sensitization that can persist for years and re-emerge under subsequent physiological or psychological stress.

This way of thinking changes how we see the illness.

Rather than clear tissue injury, Gulf War Illness may involve latent neuroimmune changes that prime the system toward maladaptive responses long after exposure.

Clinical Evidence: OEA and Functional Recovery

Recent human studies support this broader view. In a 2026 clinical trial, veterans with GWI took 200 mg of oleoylethanolamide (OEA) twice a day for ten weeks. The treatment was safe and led to clear improvements in fatigue and mood. Participants felt more energetic, emotionally better, and more able to take part in social activities. However, their pain and thinking abilities did not change much.

This pattern is clinically instructive.

OEA is a natural lipid related to PEA that activates PPARα. It is not mainly a pain reliever or a booster for thinking. Instead, it helps control metabolism, inflammation, and how the body handles stress. The specific improvements seen in the study suggest that it helps restore the body’s balance, rather than just hiding symptoms.

Participants demonstrated improved energy, emotional stability, and social functioning, while pain levels remained largely unchanged.

This is consistent with restoration of regulatory tone rather than direct analgesic or cognitive enhancement. The body’s systems become steadier before all symptoms go away.

Endocannabinoid Disruption as a Core Mechanism

Early lab studies add more support for the role of sub-optimal endocannabinoid signaling. In mice with Gulf War Illness, researchers found lower levels of anandamide in the brain and higher FAAH activity. These changes were linked to anxiety, depression-like behaviors, and trouble letting go of fear. When FAAH was blocked, and anandamide levels returned to normal, the mice’s behavior improved.

At the same time, studies of Gulf War veterans show that using cannabis in the past year is linked to more thoughts of suicide and a higher risk of suicidal behavior, even when other factors are considered. This does not prove that cannabis causes these problems, but it does show that changing the ECS should be done with care, especially in people who are more at risk.

It is therefore essential to distinguish between supporting regulatory tone and introducing psychoactive modulation, particularly in populations vulnerable to mood instability, psychosis, or substance misuse.

Clinical Considerations

Looking at Gulf War Illness as a problem of regulation changes how we think about treatment.

First, it is clear that treating single symptoms may not be enough. What needs help is how the body’s systems work together. The focus shifts toward restoring flexibility across stress response, immune signaling, sleep architecture, and neurochemical tone.

Second, the pathways that use lipids become very important. Treatments that affect PEA and OEA pathways, TRPV1 signaling, endocannabinoid balance, and PPARα activity may help with fatigue, mood, stress tolerance, and daily functioning, even if pain or thinking skills do not change much.

Third, starting with treatments that do not cause intoxication and work outside the brain may be safer depending on each patient. In these cases, optimizing ECS signaling with cannabinoid-based therapeutics or eCBome modulators that do not cause mind-altering effects can lower risk while still addressing the main problem.

Fourth, improvements are likely to happen in steps and in certain areas first. People often notice better resilience, steadier emotions, and improved daily life before they see changes in pain or thinking.

Finally, responses will vary from person to person. Factors like starting health, total stress, sex, and immune system state all play a role. Careful, personalized monitoring is essential.

A Regulatory Medicine Perspective

Gulf War Illness may be one of the best examples today of a condition caused by poor system coordination, not by permanent physical damage.

The nervous, immune, autonomic, and endocrine systems are all still there. They just are not working together smoothly.

Within this framework, the goal of care is not to override the body, but to restore its regulatory capacity. This includes supporting endocannabinoid balance, improving recovery from stress, adjusting inflammation, and building up stress resilience.

When the body’s regulation gets better, symptoms often improve too.

Gulf War Illness pushes us to look past the idea that disease is always about damage. It shows that body systems can be healthy but out of sync, and that recovery may mean bringing them back into balance instead of fixing broken parts.

For clinicians working in endocannabinoid and regulatory medicine, this is not peripheral insight — it is foundational to how recovery is understood and approached.

If you’d like to look more closely at the research behind this article — including the clinical trials, preclinical findings, and mechanistic insights — you can explore the dedicated “Gulf War Illness” dashboard on the CannaKeys platform. There you’ll find organized study summaries, clinical considerations, clinical implications, key findings, and available dosing data that provide a deeper foundation for the systems-based perspective outlined here.